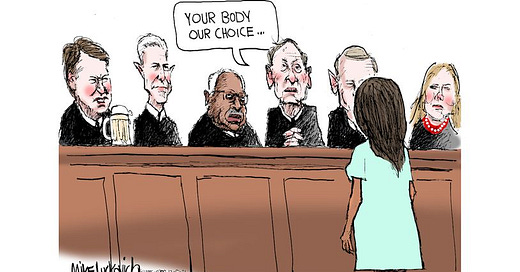

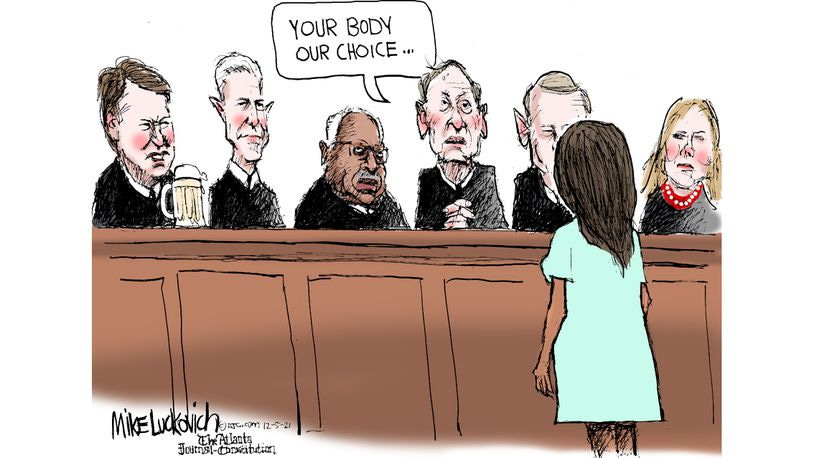

The Mississippi case Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health was argued December 1 before the U.S. Supreme Court. Thanks to Mitch McConnell’s maneuvering and Donald Trump’s court appointments it seems likely that the now current majority of avowed religious conservative judges on the court will overturn Roe v. Wade by the end of the court’s term in June of 2022. I have read a multitude of opinions about the direction of the court based on the questions asked by the judges. Hands down, the best I have read is Doug Muder’s post that I have copied below. (If you are not already subscribed to receive Muder’s “Weekly Sift,” email each Monday you should.)

Controversy over the legalization of a woman’s right to choose to terminate a pregnancy has been a part of my consciousness since I was a teenager in the 1960s. I am sure I read Justice Harry Blackmun’s majority opinion in Roe v. Wade, but after nearly half a century, I had lost the detail of the delicate, logical balancing act of his writing. Muder, by quoting Blackmun, restores that detail.

Christian religious conservatives claim there is no legitimate controversy over when life begins—for them life begins when two cells, the egg and the sperm, merge themselves and their genetic material to make a zygote—but designating a zygote as a human with the rights of a human is a construct of these conservatives’ particular religious belief—a belief that, in human history, is relatively recent and contentious. A zygote as fully human is not my religious belief, nor was it the prevailing view of the Methodist Church in which I was confirmed. The First Amendment guarantees free exercise of religion. When human life begins is a matter of religious conviction. Now at least five justices appear ready overrule my religious conviction on this point while establishing Christian conservative doctrine as the rule of the state.

Justice Blackmun rooted a woman’s limited right to chose in a right to privacy based in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (although he also nodded to a basis in the Ninth Amendment, as Muder points out below). The Fourteenth is one of the Reconstruction Amendments passed in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War that restricts “states’ rights” to infringe on a variety of personal rights. The right to privacy based in the Due Process Clause was already well established by 1973. Ominously, this same right to privacy is also the basis for Supreme Court decisions preventing states from outlawing contraception and same sex marriage. It should not escape note that many “Christian” far right Republicans would happily do away with much of the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections of individuals from invasive laws passed by state governments. Republicans are very fond of the First and Second Amendment (and, lately, the Fifth on self incrimination) but you will rarely hear a Republican announcing support for the Reconstruction Amendments. The 13th, 14th, and 15th are antithetical to Republicans’ wish to shrink the federal government and re-establish individual states’ rights of control.

Read the Weekly Sift entry I’ve pasted below for additional insight on Roe—and contemplate where this Christian extremist Supreme Court wants to go.

Keep to the high ground,

Jerry

The Roe v Wade Death Watch

Doug Muder, The Weekly Sift

Despite numerous claims during confirmation hearings that they would respect precedent, Republican justices look ready to overturn Roe.

Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health, a case that invites the Court to overturn Roe v Wade. Their decision will most likely not be announced until the end of the Court’s term in June, and comments justices make during oral arguments do not always predict what they will decide. But it sure sounded like five of the justices — Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett — were preparing to overturn Roe, while Chief Justice Roberts was looking for a way to uphold Mississippi’s Roe-violating law (that bans abortions after 15 weeks, in open defiance of Roe’s fetal-viability standard) without reversing Roe completely, thereby chipping away at abortion rights rather than instantly ending them. [1]

What is Roe v Wade? When a Supreme Court decision is talked about as much and as often as Roe has been, sometimes the original gets lost in the noise. So I went back and read Roe, which was decided in 1973. If you’ve never read it, or read it so long ago you don’t remember, it’s worth a look.

For one thing, Justice Blackmun’s majority opinion assembles an excellent summary of the history of abortion laws going back to ancient times. Anti-abortion arguments often imply that abortion has traditionally been illegal, and that only modern judicial hocus-pocus has created a pregnant woman’s right to choose that option. But in fact the opposite is true: Abortion-producing potions are as old as history, and laws banning abortions prior to “quickening” (when women start to feel the fetus moving) were rare until the late 1800s.

It is thus apparent that at common law, at the time of the adoption of our Constitution, and throughout the major portion of the 19th century, abortion was viewed with less disfavor than under most American statutes currently in effect. Phrasing it another way, a woman enjoyed a substantially broader right to terminate a pregnancy than she does in most States today. At least with respect to the early stage of pregnancy, and very possibly without such a limitation, the opportunity to make this choice was present in this country well into the 19th century. Even later, the law continued for some time to treat less punitively an abortion procured in early pregnancy.

The second thing worth noting is that Roe is a delicate balancing of rights and interests rather than the sweeping extension of judicial authority it is frequently portrayed as. On one hand, “the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision”, but a state also has legitimate interests that could conflict with an “absolute” right to abortion: “in safeguarding health, in maintaining medical standards, and in protecting potential life.”

That’s where Roe’s trimester breakdown comes from. During the first trimester, Blackmun wrote, abortion is safer than childbirth, so the state’s interest in maternal health can’t justify first-trimester restrictions. The state’s interest in potential life becomes “compelling” at the point of viability.

With respect to the State’s important and legitimate interest in potential life, the ‘compelling’ point is at viability. This is so because the fetus then presumably has the capability of meaningful life outside the mother’s womb. State regulation protective of fetal life after viability thus has both logical and biological justifications. If the State is interested in protecting fetal life after viability, it may go so far as to proscribe abortion during that period, except when it is necessary to preserve the life or health of the mother.

Where does the right to privacy come from? Any anti-abortion critique of Roe is bound to assert that the Constitution never specifically mentions the “right to privacy” that justifies a woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy. In particular, unlike freedom of speech or the right to bear arms, it’s not in the Bill of Rights.

This is an argument Alexander Hamilton anticipated in The Federalist, and why he thought including a Bill of Rights in the Constitution in the first place was “dangerous”: Oppressive governments might use a list the people’s rights to claim that anything not listed was not a right. As Edmund Pendleton wrote to Richard Henry Lee in 1788:

Again is there not danger in the Enumeration of Rights? may we not in the progress of things, discover some great & important, which we don’t now think of? there the principle may be turned upon Us, & what [government power] is not reserved, said to be granted.

The right to privacy has implications far beyond abortion, and had been recognized long before Roe, which provides a long list of previous cases that applied and developed it. One case in particular should resonate with the anti-abortion faction today: Pierce v. Society of Sisters.

In 1925, the Supreme Court struck down an Oregon law that required children to attend public schools. The law was an anti-Catholic measure targeting parochial schools. But if you search the Bill of Rights for a provision that specifically allows parents to choose a Catholic school for their children, you won’t find it. [2] That freedom to choose depends on recognizing a sphere of personal autonomy that governments can’t invade.

Roe does not argue that a right to privacy exists; that was well established by 1973. Rather, the Court concluded in Roe that

This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment‘s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment‘s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.

What about fetal personhood? Blackmun discussed this at length in Roe. He concluded that no occurrence of “person” in the Constitution could plausibly be claimed to include the unborn. If the Court was going to recognize the fetus as a person with constitutional rights, it would have to do so on its own authority. Blackmun was unwilling to claim such authority.

Texas urges that, apart from the Fourteenth Amendment, life begins at conception and is present throughout pregnancy, and that, therefore, the State has a compelling interest in protecting that life from and after conception. We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, at this point in the development of man’s knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer.

It should be sufficient to note briefly the wide divergence of thinking on this most sensitive and difficult question.

He goes on to describe views of the ancient Stoics, most Jews, and (as was true at that time) “a large segment of the Protestant community” that the moment of conception does not establish an ensouled being with the full moral value that it will have after birth.

Elaborating on that point, I will say that no branch of the US government should be making pronouncements that establish one religious position as superior to another, if there is any way to avoid doing so. The Founders had were well aware of how religious conflicts had torn England apart during the 1500s and 1600s, as one sect and then another claimed control of the government and used it to enforce their views. They wanted no such conflicts in their new country, which is why they wrote a secular Constitution.

Blackmun continues:

In view of all this, we do not agree that, by adopting one theory of life, Texas may override the rights of the pregnant woman that are at stake.

Gaslighting. Comments the justices made Wednesday underlined just how dishonest and disingenuous many of them had been during their confirmation hearings. AP summarized:

During his confirmation to the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh convinced Sen. Susan Collins that he thought a woman’s right to an abortion was “settled law,” calling the court cases affirming it “precedent on precedent” that could not be casually overturned.

Amy Coney Barrett told senators during her Senate confirmation hearing that laws could not be undone simply by personal beliefs, including her own. “It’s not the law of Amy,” she quipped.

But during this week’s landmark Supreme Court hearing over a Mississippi law that could curtail if not outright end a woman’s right to abortion, the two newest justices struck a markedly different tone, drawing lines of questioning widely viewed as part of the court’s willingness to dismantle decades old decisions on access to abortion services.

Kavanaugh in particular now makes a virtue out of breaking precedent and ignoring the principle of stare decisis.

If you think about some of the most important cases, the most consequential cases in this court’s history, there’s a string of them where the cases overruled precedent.

That string included landmark cases like Brown v Board of Education, which overturned the prior standard of “separate but equal” schools. [3]

So the question on stare decisis is why, if … we think that the prior precedents are seriously wrong, if that, why then doesn’t the history of this Court’s practice with respect to those cases tell us that the right answer is actually a return to the position of neutrality and — and not stick with those precedents in the same way that all those other cases didn’t?

Maybe he should have told Susan Collins that during his confirmation interview. Or maybe she shouldn’t have been so gullible about what he did tell her.

Dahlia Lithwick thinks it would be “refreshing” if the conservative justices’ new honesty about their intention to reverse Roe meant that the gaslighting is over

After confirmation hearings in which they promised that stare decisis was a deeply felt value and that Roe v. Wade was a clear “precedent of the court” and “the law of the land.” there’s something sort of soothing about knowing the lying to our faces will soon be over. They were all six of them installed on the Supreme Court to put an end to Roe v. Wade after all, and that is exactly what they intend to do. There will be no more fake solicitude for women making difficult choices, no more pretense that pregnant people really just need better medical advice, and no more phony concerns about “abortion mills” that threaten maternal health. There is truly something to be said for putting an end to decades of false consciousness around the real endgame here, which was to take away a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy—rape, incest, abuse, maternal health no longer being material factors. At least now we might soon be able to call it what it is.

Sadly, though, she goes on to point out that the lying continues. Now they’re gaslighting us about the significance of reversing Roe: Kavanaugh pretended that leaving abortion to the states (i.e., giving Mississippi exactly what it wants) would be a compromise. Alito claimed personhood-at-conception isn’t a religious view, because some secular philosophers agree. (Plato believed in the immortality of the soul. Does that secularize the doctrine?) Barrett opined that forced pregnancy is not such a big deal anymore, because (assuming you survive childbirth) it’s easier now to give the child up for adoption. (Why should it bother a woman to devote nine months of her life to the survival of her rapist’s genes?)

But the most extreme gaslighting concerns the implications of overturning Roe: It won’t stop there. The right to privacy undergirds, for example, same-sex marriage, gay rights in general, and the right to use contraception. All of these rights are targeted by the same theocratic faction that put Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett on the Court.

At their [confirmation] hearings, Roe was settled law, the precedent of the court. But now Roe is Plessy, which is why when the justices whisper softly that Lawrence v. Texas, Obergefell, and Griswold are not under threat today, you might wonder why you should trust them. They are all settled law—until they are not. They told us as much at their confirmation hearings and assured us today they were lying then, but aren’t lying now.

Where will abortion be illegal? You might imagine that the only immediate effect of the Court deciding in Mississippi’s favor is that their ban-at-15-weeks law would take effect. But 12 states have already passed abortion bans that are set to apply automatically as soon as Roe is reversed: Mississippi, Texas, Idaho, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Utah.

But that’s not all. Josh Marshall connects the dots between abortion and the Republican minority-rule project.

Many purple and even blue states are sufficiently gerrymandered at the state level that we should assume they’ll soon outlaw abortion too. I’m talking about states like Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio.

Wisconsin as so often is an instructive example. Wisconsin is a very closely divided state politically. It usually goes to the Democrats at the presidential level. But it’s always by a narrow margin whoever wins. The state’s governorship is similarly always close, though at the moment there’s a Democratic governor. The Democrats won the governorship in 2018 by a tiny margin. Then Joe Biden won the presidential race there by another very small margin. And yet Democrats struggled in 2020 to prevent Republicans from getting a supermajority in the state legislature. A supermajority!

Given that Republican majorities in purple-state legislatures have successfully insulated themselves from the people, all it takes is electing a Republican governor one time, and abortion rights will be gone for decades to come.

[1] Appearing to respect a law or precedent while gutting it in practice is a very Robertsy thing to do. For example, he didn’t strike down the Voting Rights Act in 2013, he just eliminated the government’s main tool for enforcing it.

If you look at the broad sweep of Roberts’ career, he wants to achieve partisan objectives without tarring the Court’s non-partisan image.

[2] You also couldn’t claim that the Founders intended to include such a protection. Some of the Founders were virulently anti-Catholic. In a 1774 letter to Parliament, which I believe was written by John Jay, the Continental Congress described Catholicism as “a religion that has deluged your island in blood, and dispersed bigotry, persecution, murder and rebellion through every part of the world.”

[3] It’s worth pointing out that the Court didn’t reverse the Plessy standard of separate-but-equal just because the 1954 justices had different views than the 1896 justices. The intervening half-century had brought a long series of cases to the Court in which states claimed that their segregated schools were “equal”, but they really weren’t. In Brown, the Court concluded from experience that the Plessy standard wasn’t workable; separate schools for Black students were always going to be unequal.

Nothing similar has been happening with respect to Roe. The only difference between 2021 and 1973 is that different people are on the Court.